Changes

Memories of the War years

‘When I was 2 years old I caught pneumonia, and that in turn triggered mild asthma. I remember very little of the first attack, only that Mum carried me for long spells in her arms while she sang for me. A song about a field mouse who made a bike out of a nutshell.

That asthma attack didn’t last long, and my health became relatively normal again. Until, years later, by the end of the war, I got hunger oedema and other effects of starvation. When I arrived in Switzerland, shortly after the war, my foster mother explained in sign language that I had to eat so much that I could no longer encircle my upper arms with one hand.’

‘You mean like you can encircle your wrist with one hand? You could do that to your upper arms?’

‘Yep, that’s right. Not overly massive biceps then, were they? Anyway, the asthma never got very bad until well after the war.

When the only medicines were adrenalin or a potassium bromide solution.

When we heard more and more details from the camps.

When much of what we had known for years was gradually confirmed.

When I began to be haunted by my memories of the war years.

Then, when Dad had his electroshock treatment, the doctor suggested I might go and stay for a while with our good friends in Haulerwijk. With Pake and Beppe, and with Uncle Eb and Uncle Freerk. And again they came to the rescue. No war danger this time, but they were just as generous. Again I could work on the farm with Nestoria, or swim in the canal, or sit and read on the front lawn, where I could see – but never talk with – a teenage girl who sat reading on the neighbours’ front lawn. She sometimes looked in my direction, but was to shy even to nod. Maybe she too had bad memories?

Looking at her brought Greetje back to my mind. Greetje, my first big love, not how she was when we met again after the war, but how she had been while we were close friends.

I was changing in those days in Haulerwijk, changing fast.’

‘Well, you were a teenager then, weren’t you, Grandpa? Of course you were changing. I changed a lot when I became a teenager.’

‘There was more to it than that, Tracy. I had lived away from home so often, and for such long spells, that I had learned to be my own counsel, to be independent.

And on top of that, I had had to act more than my age during the war. Even when I was only eleven there had been times when I was the oldest one at home. When Mum was away on Hunger Trips for days on end, scouring the countryside for food, like thousands of other Amsterdammers, and Dad was away filling in bomb craters at the airport, or working with a lot of others digging a lake near Amsterdam as slave labour. Those days I did the cooking and cleaning and changing the nappies of my youngest brother. Trudi, at 9 years of age, had to chip in too, helping me with the dishes and the shopping.

Maybe I became too independent, went my own way too much. I had plenty of good friends, but they tended to push me into a kind of leader role. I didn’t like it, but didn’t know what to do about it either.

My hobby became biology, in particular marine biology. So, I joined a rather special nature study club, the NJN, the ‘Nederlandse Jeugdbond voor Natuurstudie’. Their most important rule was that none of the more than 2000 members could be older that 23. No adults allowed ever, not as leaders either. The club was divided into districts and subdivided into smaller local groups. My group was centred around Alkmaar and pretty soon I got pushed onto the committee.

Every weekend we held an ‘excursion’ - usually along the beach or through the sand dunes - looking for strange sea beasties or counting birds or trying to find rare plants. I loved it. All the members were real individuals in my eyes, not like those sissy regimented boy scouts. We often stayed away the whole weekend and camped in the coastal reserve, where nobody was allowed to be after sunset, and where nobody was allowed off the footpaths. And camping was even more against the law. But how else could we observe owls and other night birds, or watch the sea phosphorescing?

I never saw myself as a rebel though. It never occurred to me to want to change things; I simply ignored rules and whatever else I didn’t agree with. I could see the need for traffic rules, so I obeyed those. I could see no reason why I should pay to be in the forest by daytime – stay on the footpath only, by order of the council! – and why we were not allowed to stay in that same forest overnight ever, or even worse, why we would need a camping permit even to stay on public camping grounds. Other people obediently got their camping permits and some, like Trudi, even sat exams to gain a camping passport, which allowed them to camp on the land of some farmer. And even that farmer had to have council permission to let people with camping passports stay on his land overnight.

I just went my own way, as simple as that. Why bother with all those rules?

There were still the remains of the German Atlantic Wall: miles and miles of concrete tunnels under the dunes, with large bunkers at regular intervals. In winter those bunkers were ideal to camp in. I started it, my friends followed. Apart from our group, nobody ever went there at night, so we could safely light our cooking fires and play music or even do folk dancing. We went back to the old ways, much like other people some decades later in the rest of the world. We sang the old songs and danced the old dances.

By then I had my first musical instruments, a descant and a tenor recorder. I particularly remember a moonlit night when I had gone out on my own after the others had fallen asleep. I had lifted my pushbike out of the tunnel and pedalled along the footpaths for hours. Riding without hands so I could play the tenor non-stop. Magic.

That period was one of the last major shapers of my personality.

What turned out rather important too was a kind of interlude a few years later, after I graduated from the Art Academy. I had a position as part time art teacher at an experimental art school, and I had asked to have my hours cut down to the absolute minimum. Just enough to pay for my rent and food. I’ll tell you later about all that, but the main thing then was that I felt I needed a chance to think over all I had learned and experienced. While I was a student there never seemed to be enough time to do more than accumulate knowledge, and I wanted to sort myself out.

Three months I took off. For three months I thought, looked at trees, at the sea, wrote poems, played music and took photographs. Those three months have helped me for the rest of my life.

There were two more big events that made me into the person I am now: marrying Karen and the birth of our son Luigi. After that there were more a gradual developments and changes, but nothing as drastic. Or maybe there were, but in a different way. More planned and thought out beforehand.

So there you are, that’s me.

I had survived the war. And I had found the most amazing role models. Not that I ever thought in those terms, they were simply people I had great respect for.

My parents, who never gave up, and the family in Haulerwijk, who had hidden me and protected me in spite of the risk.

Uncle Herman, who taught me the basics of painting and Opa, who started me on woodcarving.

The chemist lady, who gave her life so Oma and Uncle Herman could escape and live.

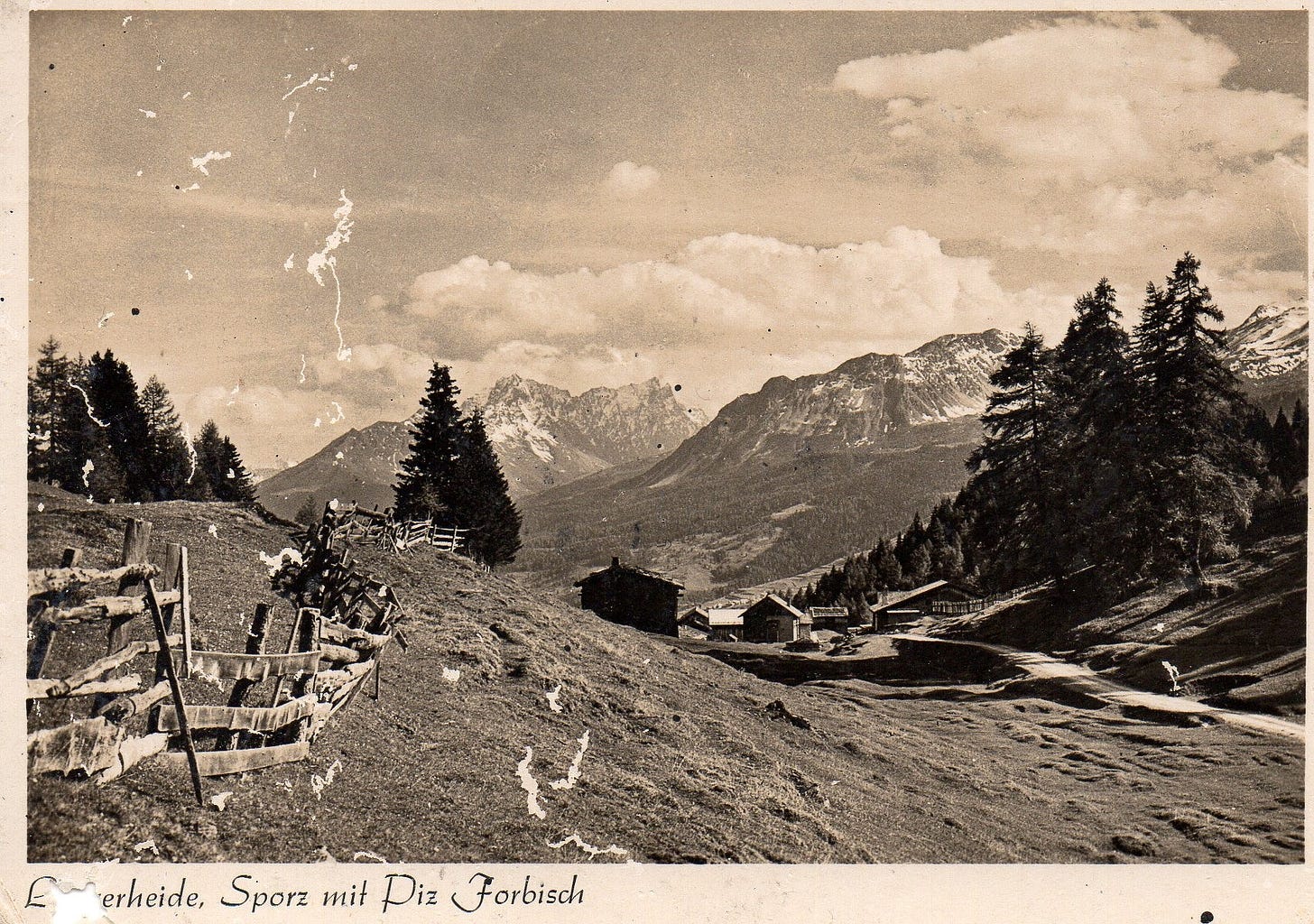

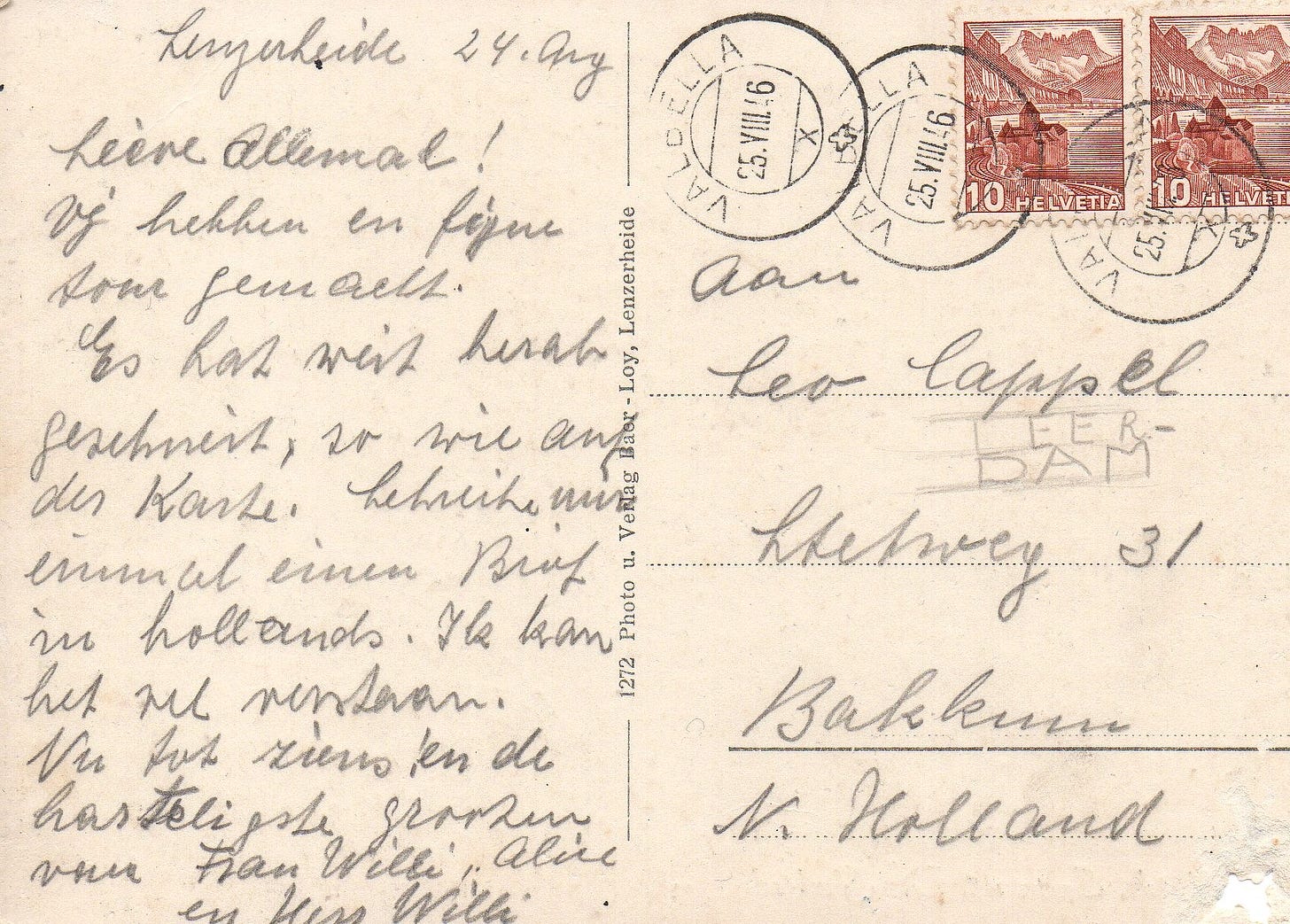

In particular also my Swiss foster mother, who kept sending postcards for years after, and finally, the man in Germany whose name I never knew, but who gave me a ride and a meal, and who, in those few hours, showed me the way to stop hating.’

Wow. I need to say I have studied, and more importantly, learned and continue to learn about the Holocaust. I cannot thank you enough for sharing. It's a horrific period of time, but also an incredible story of humanity. I've read many memoirs, but to hear it so directly is a real gift. Thank you Sir.